Foto

Un grupo de desplazados internos reza a primera hora de la mañana en un campamento de la selva donde se esconden de las fuerzas indonesias.

Décadas de represión en Papúa Occidental obligan a los habitantes al desplazamiento forzado

Desde la década de 1960, la población indígena de Papúa Occidental ha soportado una ocupación colonial represiva fuertemente militarizada y extractiva por parte de Indonesia. Se le ha llamado “la Palestina de Indonesia” y se ha calificado de “genocidio en cámara lenta”.

Juan Patricio Gavilan *

Junio 2, 2023

Durante décadas se ha prohibido el acceso a la región a periodistas extranjeros y se ha expulsado a organismos de las Naciones Unidas y a organizaciones humanitarias y de derechos humanos. Sistemáticamente se violan las libertades fundamentales, como la de expresión, y los periodistas locales comprenden la gravedad de los riesgos que entraña criticar a las autoridades indonesias o hablar de autodeterminación. El resultado es un velo de silencio sobre una crisis humanitaria y de derechos humanos masiva y de larga duración que continúa en desarrollo.

La historia de Rahel Taplo no es extraña en el contexto de Papúa Occidental. Vivía con su familia en una aldea llamada Kiwi, en el altiplano central. En septiembre de 2021, “cuatro helicópteros lanzaban morteros sobre las casas y oíamos disparos, así que todos corrimos, nos adentramos en el bosque”, cuenta Rahel. En este ataque, las fuerzas indonesias destruyeron y dañaron viviendas y edificios públicos del pueblo. Rahel Taplo y los demás habitantes de la aldea huyeron a zonas remotas de las selvas circundantes, donde se han escondido para evitar ser detectados desde el día del ataque aquel septiembre de 2021.

Testigos de la aldea añadieron que se vieron dos drones durante el ataque, uno lanzó morteros y el otro presumen que era para vigilancia. Posteriormente, en toda la aldea, se recuperaron proyectiles de mortero de 81 mm sin detonar, así como granadas y casquillos de proyectil M-16.

Las fuerzas especiales indonesias ocupan ahora posiciones en Kiwi y han establecido un puesto de francotirador que explora la zona con miras láser verdes visibles día y noche. Tres habitantes de Kiwi fueron asesinados por los francotiradores cuando intentaban recuperar alimentos o animales de sus granjas.

En el refugio de la selva donde vive Taplo hay más de 200 personas que huyeron de Kiwi, pero este es sólo uno de los siete refugios similares en la zona. Los aldeanos siguen teniendo demasiado miedo como para regresar a sus casas y granjas, la intimidación constante hace que no piensen en volver, así que no les queda más remedio que cazar cerdos salvajes y cultivar un poco de raíz de taro cerca de los arroyos para alimentarse.

Rahel Taplo y los demás habitantes de la aldea huyeron a zonas remotas de las selvas circundantes, donde se han escondido para evitar ser detectados desde el día del ataque aquel septiembre de 2021.

Mapa: Revista Espacio

Viven en chozas improvisadas hechas con palmas. Rahel habla de cómo echan de menos sus casas, el dispensario y la escuela. “Tanto hombres como mujeres y niños sufren”, dice, “sin acceso a los servicios sanitarios las mujeres en el parto y los bebés sufren mucho”. A pesar de las grandes necesidades, no hay acceso a la ayuda humanitaria. Taplo dice, simplemente, “estamos solos”.

Es difícil determinar la verdadera magnitud de los desplazamientos provocados por la violencia en este país, ya que no se dispone de estadísticas del gobierno de Indonesia y se niega el acceso a las organizaciones que normalmente elaboran esos datos, como ACNUR. La Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos ha cifrado recientemente el número de desplazados internos entre 60.000 y 100.000 personas.

La industria extractiva se beneficia del desplazamiento forzado

Cuando los indígenas papúes se ven obligados a abandonar sus tierras por las operaciones militares, dejan paso a industrias extractivas como la minería, las plantaciones de palma y la tala de árboles por empresas indonesias e internacionales y, también, por colonos indonesios procedentes principalmente de Java y Sulawesi.

Aunque las estadísticas del gobierno indonesio son secretas, se cree que más de un millón de indonesios han sido llevados a la región en el marco del programa transmigrasi patrocinado por el Estado, y la población indígena de Papúa Occidental ya se ha reducido drásticamente. Algunos expertos califican esta reducción sistemática de la población indígena de Papúa de “genocidio en cámara lenta”. El impacto sobre la demografía también tiene un efecto destructivo sobre la lengua y la cultura de la región.

La Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos ha cifrado recientemente el número de desplazados internos entre 60.000 y 100.000 personas.

El racismo contra los papúes occidentales va desde insultos comunes como “monyet”, que significa mono, hasta formas más activas de discriminación. Los inmigrantes indonesios son propietarios de la mayoría de las tiendas y negocios de Papúa Occidental, muy pocos papúes lo son, y los empleados papúes son enormemente superados en número por los inmigrantes indonesios. Los bancos deniegan a los papúes préstamos para abrir negocios, lo que limita sus oportunidades empresariales, y muchos papúes sienten que no reciben un trato igualitario por parte de los funcionarios del gobierno. En resumen, los papúes se sienten ciudadanos de segunda clase en su propia tierra.

Human Rights Watch y Amnistía Internacional han condenado los violentos ataques contra manifestantes en Papúa Occidental. Hay muchos casos documentados de uso excesivo de la fuerza por parte de las fuerzas de seguridad indonesias contra manifestantes pacíficos, incluidos casos de disparos mortales, palizas, detenciones arbitrarias, desapariciones forzadas y ejecuciones extrajudiciales. Incluso izar la bandera Morning Star, símbolo de la identidad cultural de Papúa Occidental, es un delito de traición castigado con largas penas de prisión.

Naciones Unidas ha expresado su preocupación por el acceso de los observadores de los derechos humanos a Papúa Occidental, ya que se han enfrentado a dificultades y restricciones en sus esfuerzos por investigar los abusos contra los derechos humanos y proporcionar asistencia a la población local. La ONU ha pedido reiteradamente al gobierno indonesio que permita una vigilancia independiente e imparcial e investigue las denuncias de violaciones de derechos humanos en la región.

Construir un movimiento unificado de oposición a la ocupación indonesia, un movimiento por la autodeterminación frente al dominio indonesio, en una región con 276 lenguas, así como con un acceso extremadamente difícil a muchas comunidades, plantea especiales dificultades.

Cualquier avance en el debate sobre la autonomía o la independencia también se ve obstaculizado por la falta de entendimiento entre facciones con historias y planteamientos diferentes, lo que hace que muchos jóvenes piensen que la única vía es el Ejército de Liberación de Papúa Occidental (TPN-PB), un movimiento separatista descalzo y mal armado. La situación en Papúa Occidental sigue siendo tensa y, a medida que continúan la exclusión y la represión, aumenta la desesperación.

El caso de Rahel Taplo, en Kiwi, se repite en las regencias de Nduga, Puncak, Intan Jaya, Maybrat, Pegunungan Bintang y Yahukimo. Decenas de miles de papúes están abandonados en remotos campos de desplazados sin servicios básicos ni vivienda adecuada, sin acceso a la sanidad, la educación o el empleo.

Como ha dicho a menudo el líder independentista de Papúa Occidental en el exilio, Benny Wenda: “Papúa Occidental es una colonia y ya es hora de que seamos libres. Nuestro pueblo sufre cada día. El mundo debe escuchar nuestro grito de ayuda”.

On 16 September 2021 the village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

Logging activity in the Taja region of Papua includes logging by large companies that build their own sawmills with kitchens and living accommodation, and these camps move periodically through the jungles as the supply of trees declines. All of this logging has government-provided military and police security and makes use of heavy plant such as 16-wheel logger trucks, bulldozers, excavators and they build roads through the jungle to make access and extraction possible. In addition to these large-scale operations there are smaller-scale operations targeting smaller trees and using rudimentary equipment. In the Taja region these operations are run by officials of the Indonesian Special Forces who provide security to many local loggers, often one-man operations, who bring square timber – cut only by chainsaw – to the roadside for collection. The square timber is taken at night by lorries carrying shipping containers and going straight to the shipping port of Jayapura. Some of the loggers are paid only in rice or other food, others are paid in cash, but paltry sums.

On 16 September 2021 the village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

On 16 September 2021 the nearby area of Kiwi and Kiwirok was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

When the villages of Kiwi and Kiwirok – in Pegunungan Bintang Regency, near the PNG border – were attacked by helicopters and mortar fire from the Indonesian Army and Special Forces, many houses and building were destroyed or damaged and the inhabitants fled into the surrounding jungle for safety. Alut Bakon is one of the jungle areas where Internally Displaced People have taken refuge. There is no education and no health service and there is no access for humanitarian organisations or support.

The village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

On 16 September 2021 the village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

Logging activity in the Taja region of Papua includes logging by large companies that build their own sawmills with kitchens and living accommodation, and these camps move periodically through the jungles as the supply of trees declines. All of this logging has government-provided military and police security and makes use of heavy plant such as 16-wheel logger trucks, bulldozers, excavators and they build roads through the jungle to make access and extraction possible. In addition to these large-scale operations there are smaller-scale operations targeting smaller trees and using rudimentary equipment. In the Taja region these operations are run by officials of the Indonesian Special Forces who provide security to many local loggers, often one-man operations, who bring square timber – cut only by chainsaw – to the roadside for collection. The square timber is taken at night by lorries carrying shipping containers and going straight to the shipping port of Jayapura. Some of the loggers are paid only in rice or other food, others are paid in cash, but paltry sums.

On 16 September 2021 the nearby area of Kiwi and Kiwirok was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

On 16 September 2021 the village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for survellance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors, ICRC and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

On 16 September 2021 the village was attacked by air by Indonesian forces destroying and damaging many houses and public buildings including a clinic and church. People from the village fled into the surrounding jungles. According to eyewtinesses from the village who are still living in camps in the jungle, two drones operated during the attack, one for surveillance and one armed with explosives. Helicopters and mortars were also used during the attack. Unexploded 81mm mortar rounds were recovered by the villagers from across the village. Indonesian forces occupy positions closeby and continue to attack and intimidate the village. According to eyewitnesses, three people returning to the village have been shot dead by Indonesian sniper fire from Kiwirok since the attack in September 2021. The villagers remain too afraid to return to their village and farms and they eke out an existence in the jungle. Visits from human rights monitors and humanitarian groups have been prohibited by Indonesia.

* Fotoperiodista independiente

Más Fotos

-

Mentiras verdaderas. El paisaje

José Cabezas es un fotógrafo salvadoreño-estadounidense radicado en San Salvador, El Salvador que, desde 2014, trabaja como fotógrafo contratado para la agencia Thomson Reuters con…

-

«Prohibido olvidar»

Las imágenes captadas por el fotógrafo militante italiano Giovanni «Gió» Palazzo son, para este propósito, más que apropiadas, especialmente las expuestas en este momento en…

-

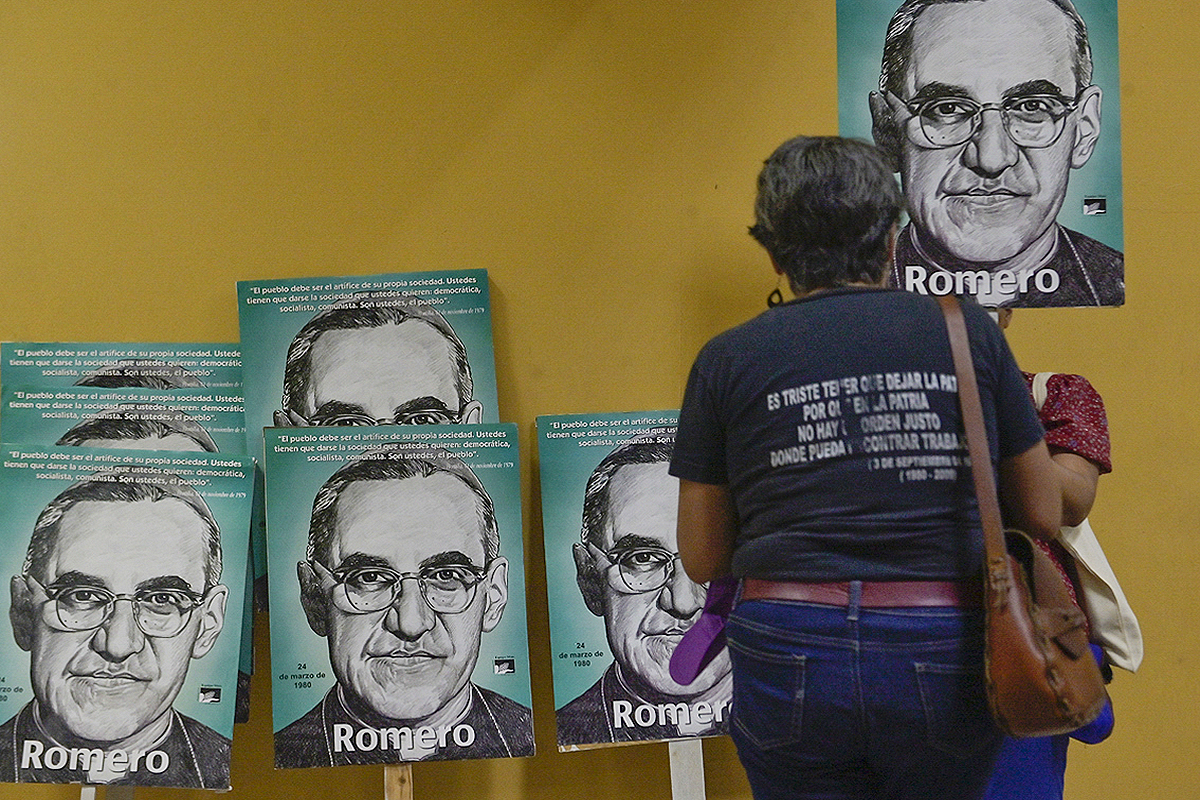

¿Qué diría hoy Monseñor Romero?

El pasado domingo 24 de marzo hubo un sol inclemente. No obstante, feligreses fieles a la memoria del arzobispo mártir salieron cerca del mediodía a…

-

Magnicidio a 35 metros de distancia

El suave ronroneo del carro nuevo VW Passatt color rojo, no perturbó la atención de los pocos fieles que asistían a la misa. Amado Garay estacionó el…

-

El cultivo del pensamiento crítico ante la desinformación

En una atmósfera cargada de información, desinformación e información falsa no caería mal que desde la propia práctica en círculos familiares y sociales se haga un esfuerzo por…

-

Introducción o introspección

Al contrario de lo que creí en este encierro forzoso por el COVID 19, he mejorado la salud mental; ahora, nada cohibido, platico fluido entre Yo y Mí… Acá les comparto uno…

-

Pobrecito poeta, capítulo 2

—Vaya, vine temprano (estornuda). Mi nombre es Roberto del Monte, y vengo arrastrándome, como decía el prócer José Simeón Cañas, medio de goma, y si estuviera agonizando,…